BIRDS AND BEEF. CAN’T HAVE ONE WITHOUT THE OTHER.

Ranchers are stewards of the land, ensuring grasslands and forages are good quality and subsequently providing habitat for wildlife. Marshall Johnson, chief conservation officer for National Audubon Society, says cattle, birds and grasslands form a symbiotic relationship to the point of “no cows, no grass, no birds.”

“If we were going to actually address grassland bird declines and grassland loss, we really needed to find creative ways of supporting the people who are the primary stewards of this ecosystem, and that’s cattle ranchers,” Johnson told WLJ.

According to Audubon, 84 percent of American grasslands are on privately owned land and 95 percent of all grassland birds live on cattle ranches. Grasslands are the most threatened biome, with nearly 720 million birds lost to urban and agricultural development since the 1970s — a 40 percent decline.

To combat the negative effects of grassland degradation, Johnson and others at Audubon began a journey in 2017 with grassland managers, ornithologists and other land managers from several agencies to create Audubon’s Conservation Ranching Initiative (ACR).

Johnson noted if the Audubon name was going to be associated with cattle production, there needed to be a certification program that would establish a “standard that could not only lead to increased outcomes for the livestock associated with the ranch, but also obviously the wildlife and the birds, and the ecosystem services that grasslands can and do provide.”

Participants in ACR are able to market their cattle and beef as “grazed on Audubon-certified bird-friendly land,” adding value to their operation and connecting them to premium consumer markets. To date, the program has enrolled over 70 ranches and 2 million acres. In June, Audubon announced it partnered with Panorama Organic Grass-Fed Meats, which will add nearly a million acres to its ACR program.

Rafter W Ranch

Situated on gently rolling hills on Colorado’s Highway 86 outside Simla, Rafter W Ranch has grown from a couple of head raised in a small lot for health reasons, to a 1,000-acre operation with a budding direct-to-consumer business of beef, lamb and chicken.

After purchasing 100 acres in 2014, Lance and Lisa Wheeler began experimenting with genetic profiles of breeds that did well on grass, and looked at flavor and fat profiles. Today, they are experimenting with crossbreeding Dexter cattle for their marbling and moderate frame size, and Angus for their carcass quality. Currently, Wheeler has 96 head in a breeding program and in a separate meat program.

He first heard about the ACR program about four years ago at a Grassfed Exchange conference. At the time, the program was in a few states, but was expanding to Colorado.

“We’ve been pretty conscious about what else we were sharing our space with, but we didn’t have an appreciation about the pressure — especially on grassland birds — of the push of urban development into rural space,” Wheeler told WLJ.

“And I didn’t realize some of my favorite birds in the spring, how much pressure they’re under. I didn’t have an appreciation for quite how many birds nest on the ground.”

Eventually, Wheeler was put in contact with Dustin Downey, conservation ranching coordinator for Audubon Rockies, and together they worked on the ranch’s Habitat Management Plan (HMP). Wheeler said the process of putting together an HMP was fairly easy as the ranch was already implementing holistic management. It was understanding “how much force do different birds need, where do we need to make deferrals and at what times of the year and why.”

Wheeler noted 90 percent of the ranch is generally in a deferral space, so some practices stipulated in the HMP, such as having a 50 percent deferral space from nesting birds, was not a problem. The biggest uncertainty for Wheeler was the first-year audit in the fall with the third-party auditor Food Alliance.

Wheeler said the auditors were able to offer advice on areas of improvement and give him an idea of where the ranch needs to go and where they are going. The only pushback on the recommendations was to source organic hay, Wheeler said, as it “takes cost to a whole new place.” The ranch is not certified organic and it is not required as part of ACR.

Wheeler said there have been very little out-of-pocket costs to participate in ACR and even recently installed a solar-powered well with gravity feed through a cost-share grant from USDA’s Environmental Quality Incentives Program. Wheeler also noted the ranch is part of an ACR grant in Colorado for a habitat improvement program.

When asked about a return on investment, Wheeler said he didn’t start as a traditional cow-calf operation and grew the direct-to-consumer business from the ground up, so it is difficult to quantify a return. He noted the ACR and grass-fed community is tightly knit, so if a rancher has a question or needs advice, it is easy to contact someone.

His advice for ranchers interested in the program is to look at their practices, such as rotational grazing and high-density stocking rates. Wheeler noted that working with Audubon is a long-term process when developing an HMP for your ranch. They will look not only at grazing practices, but deferral space, weed problems and other items that affect the landscape, such as bird-friendly practices as time progresses.

Wheeler said with holistic management, there are always issues on the ranch and you are always asking yourself, “What did we do well and what things can we improve upon?”

Return on Investment

Johnson said a return on investment is hard to quantify as the program and label have been “live” for only a few years and the last 18 months have been abnormal due to the pandemic. He did provide a snapshot of one of the markets where at the time, conventional hanging carcass weight was $1.72/lb., grass-fed beef was roughly $2.30/lb. and Audubon-certified beef was $2.80/lb.

Johnson noted they would like to get where they can measure the difference between conventionally raised beef and what someone can expect from the conservation program.

“Not every one of our ranchers has access to that premium, but that’s what we’re working toward,” Johnson said. “We’ve made some pretty major investments in growing the market and communications of our conservation ranching certification.”

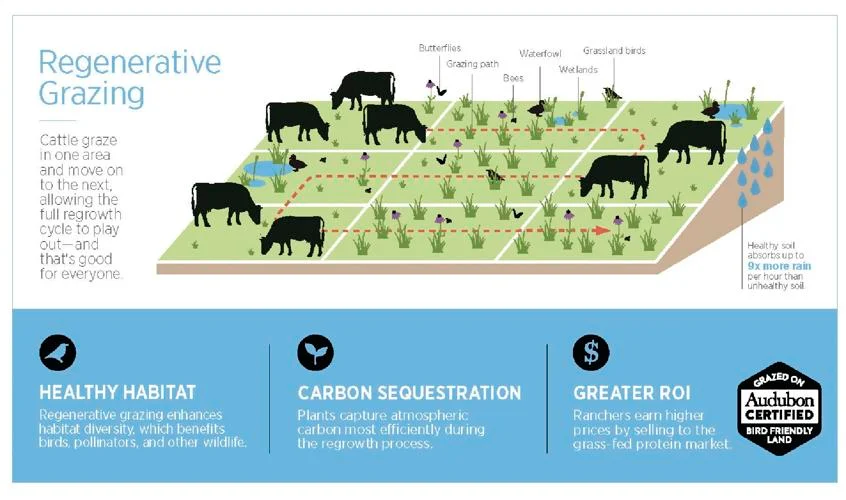

Practicing regenerative agriculture with healthier soils and native vegetation combined with multi-paddock grazing leads to better availability of forages which may help in drought.

“Incorporating and healing the land and bringing back those native forages—it’s beneficial for birds, absolutely,” Johnson said. “But it’s also really beneficial for the ranches and having that available forage, whether it’s a drought year or not.”

While Johnson noted it is impossible to escape a drought this deep in 2021, the forage composition is healthier on ACR lands as cool-season grasses and other natives have taken over in ACR ranches in the Northern Plains.

Downey expounded on the non-monetary aspects of return on investment in the networking of other ACR ranchers. He said Audubon conducted “Ranching for Profit” workshops that were concentrated on grazing, but the focus was, “How can you as a producer both be better for the land but also gain monetary value through production?”

Johnson said Audubon recently surveyed participating ACR ranches and found a vast majority were satisfied with how the protocols were designed and their enrollment in the program.

“Despite the positive feedback we’ve received, we have a lot of work to do, and we’re really encouraged about what we’ve been able to accomplish for the first five years,” Johnson said.

“If we are to encourage and support the sustainability of high-quality, sustainable beef production, it’s not just dollars and cents, it’s the quality of life as well. And we want to make sure that a program like this encourages those changes, those adaptations that lead to a better quality of life.”

Certification for the Audubon Partnership

Ranchers do not pay to participate. Each participating ranch develops a Habitat Management Plan (HMP) with Audubon to address site-specific habitat and bird conservation opportunities.

Program certification consists of the HMP and four protocols: environmental sustainability; habitat management; forage and feeding; and animal welfare and husbandry. In addition, producers are expected to adopt regenerative soil health practices. The five soil health practices include: keep the soil covered; limit biological disturbance; encourage plant diversity; keep living roots in the soil as long as possible; and use livestock as a tool to build soils. Plans can be modified and changed over time to address the rancher’s objectives. Johnson said Audubon provides a cost share of up to 80-90 percent on infrastructure to practice regenerative grazing, water system development and invasive species control.

Certification is conducted by the third-party Food Alliance, which ensures compliance with the protocols within applicable Audubon Conservation Ranching Standards that are required and suggested. Annual audit fees are currently paid by Audubon and on-site audits typically take about four to six hours.

Feedlots, antibiotics (except for topicals), growth hormones, GMO feed, and animal byproducts in feeds are not allowed. In-pasture feeding of grain and/or high-energy feedstocks is allowed as an interim measure during adverse weather, immediately pre- and post-calving, and/or the final 90 days before slaughter. The use of insecticides, pesticides, herbicides and fungicides are not allowed unless exceptions were marked in the HMP.

The suggested protocols are aimed at continual improvement. Operators must show progress in meeting the suggestions with each audit until at least 75 percent of applicable suggested protocols are achieved within 10 years. Failure to meet these requirements will lead to the denial or withdrawal of certification for the audited ranch. A detailed list of the protocols can be found at Audubon.org/ranching/protocols.

The application is separate from the HMR and consists of a certification agreement detailing rights and responsibilities; declaration of integrity, which ensures the chain of custody is maintained throughout the supply chain from animal to slaughter; and a purchased animal affidavit, which states a non-ACR animal has not been treated with antibiotics or ionophores in feed.

Certification is also measured on the “bird-friendliness index,” a metric created by scientists and a peer-reviewed tool for quantifying grassland and arid land bird community response to management. Audubon conducts a survey on the first year and subsequently every other year and measures bird abundance, diversity and resilience on ACR ranches. The data is then compared to livestock operations in the same area. Preliminary data for ACR-enrolled ranches in the first five years shows that “on average grassland bird abundance has increased by a third versus non-ACR ranches,” according to Johnson.

While obtaining certification and compliance may sound difficult, Downey, conservation ranching coordinator for Audubon Rockies, told WLJ some producers are already in compliance, and some are almost there prior to certification. Downey’s goal is to provide technical assistance and “to move a producer from where they want to be… and put our focus into helping them get there.”

ORIGINAL ARTICLE: https://www.wlj.net/top_headlines/magazines/birds-and-beef-a-symbiotic-relationship/article_eb9b86b2-01d2-11ec-9f94-b7d35a9e40a1.html